Comments/Context: Looking at the lesser known early work of an established artist is a bit like going on a treasure hunt. Made before the artist likely settled into his or her mature style, these images often feel fluidly rough, unfinished, and experimental, and seen with the benefit of hindsight, tantalizing hints of what would come later can be seen peeking through. In many cases, an artist needs to work through some major influences first, unpacking their merits and determining which parts can be repurposed for their own use, so early periods are sometimes a methodical exercise in sifting through the echoes and connections of teachers and heroes, in search of the genuinely original voice underneath. But early production is just as often made with an untainted freshness, the without-a-net risk taking coming naturally from the very beginning. In both scenarios, opening the long sealed boxes and examining what happened at the start can be a critical part of building a larger and more comprehensive narrative arc for an artist’s career.

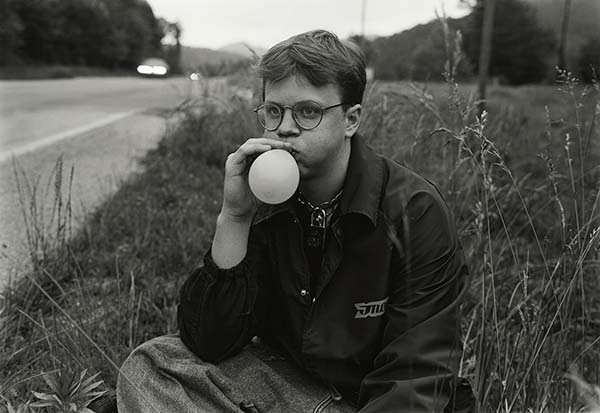

This lushly produced photobook heads back to 1983, when a 21 year old Mark Steinmetz left art school at Yale and headed west to California (his pre-selfie self portrait graces the cover). A short preface to the book sets the scene – Steinmetz living in a tiny roach-infested apartment, running into Garry Winogrand at a local camera shop, and ultimately seeing Winogrand around town enough that they started t0 drive around together in Steinmetz’ champagne-colored Fiat taking pictures. While Winogrand never looked at Steinmetz’ photographs (and subsequently died just a year later), for a young artist trying to find a path in photography, cruising Los Angeles with a master (Steinmetz’ driving so Winogrand could shoot out the window) must have been quite a thrill.

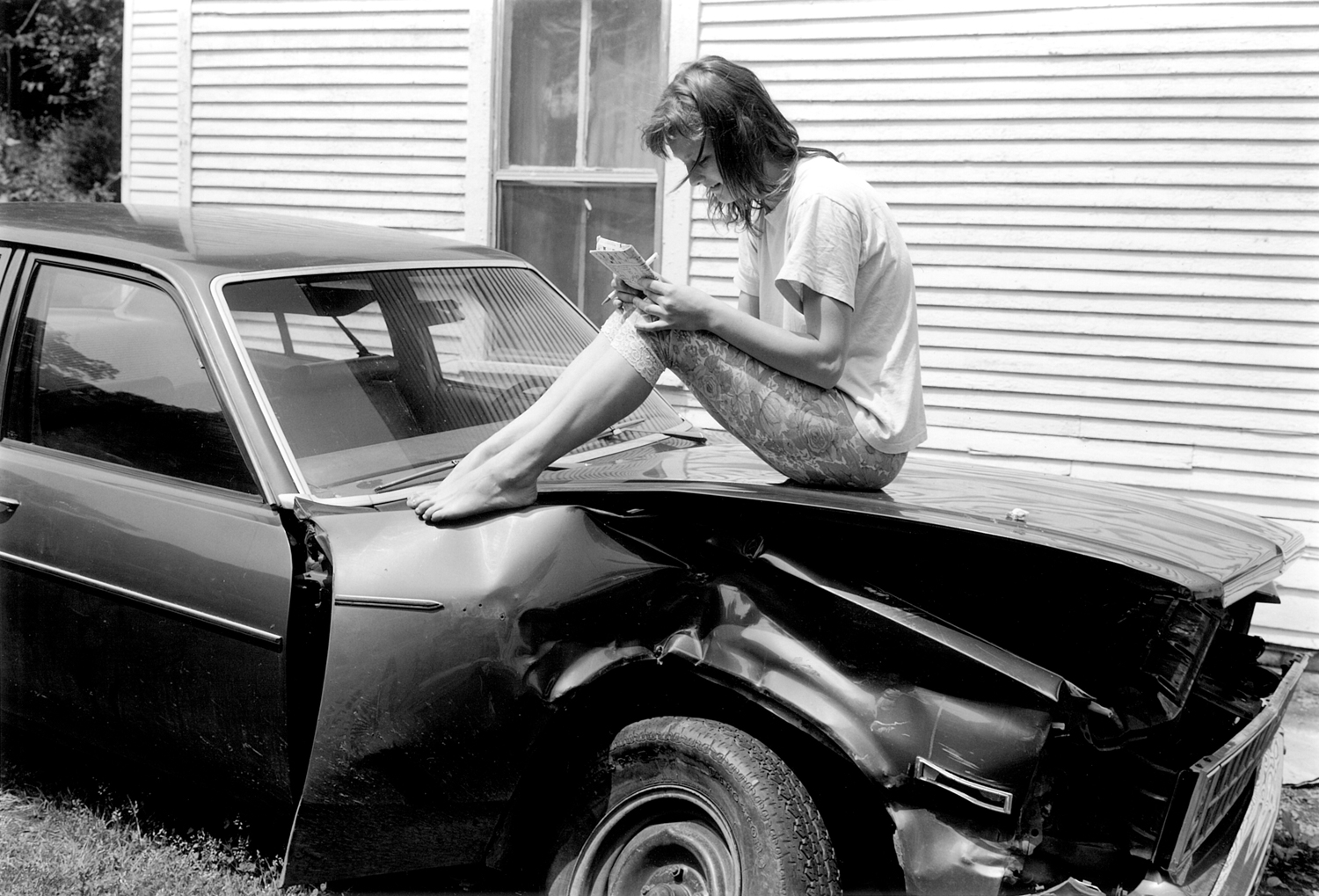

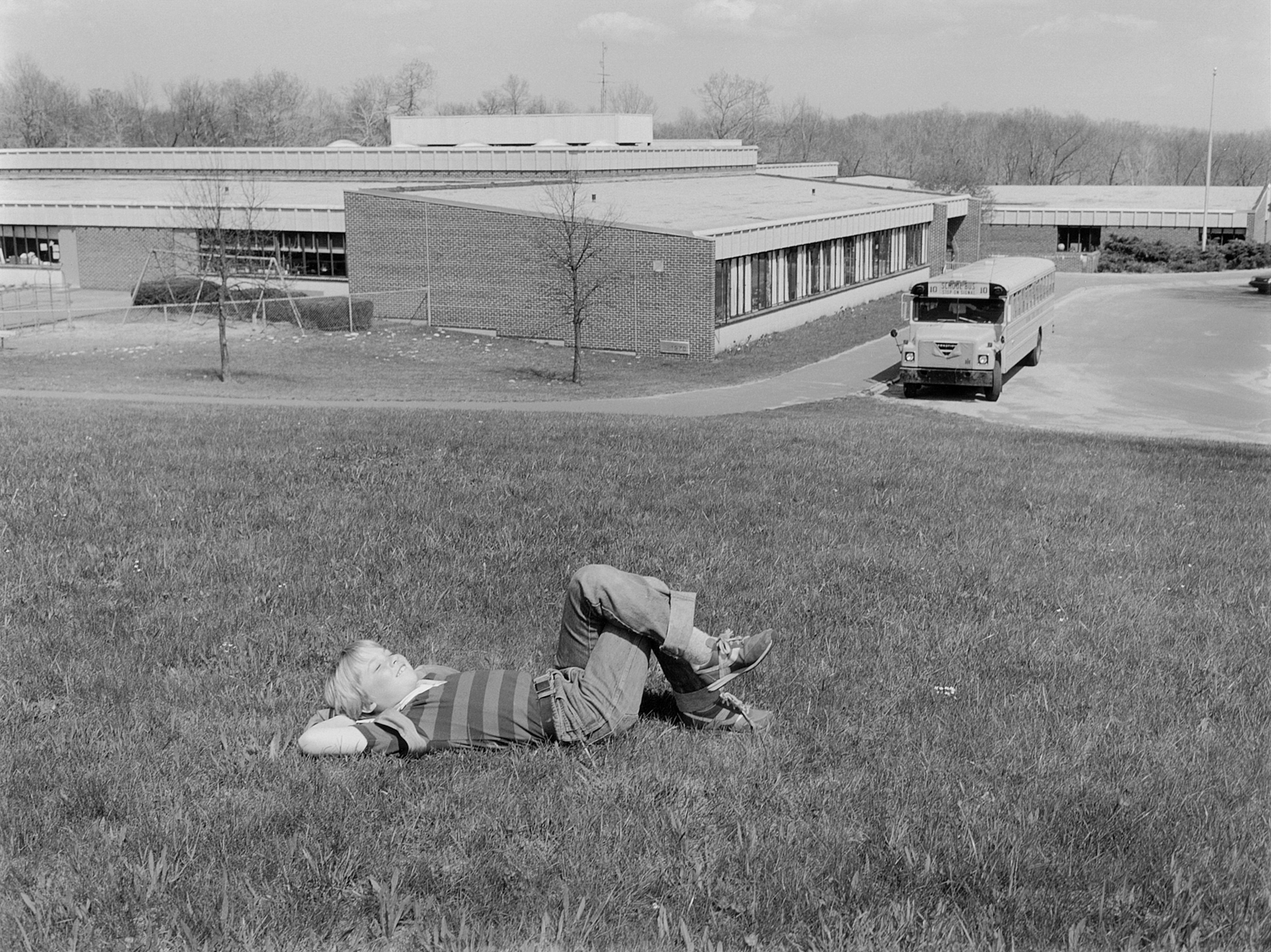

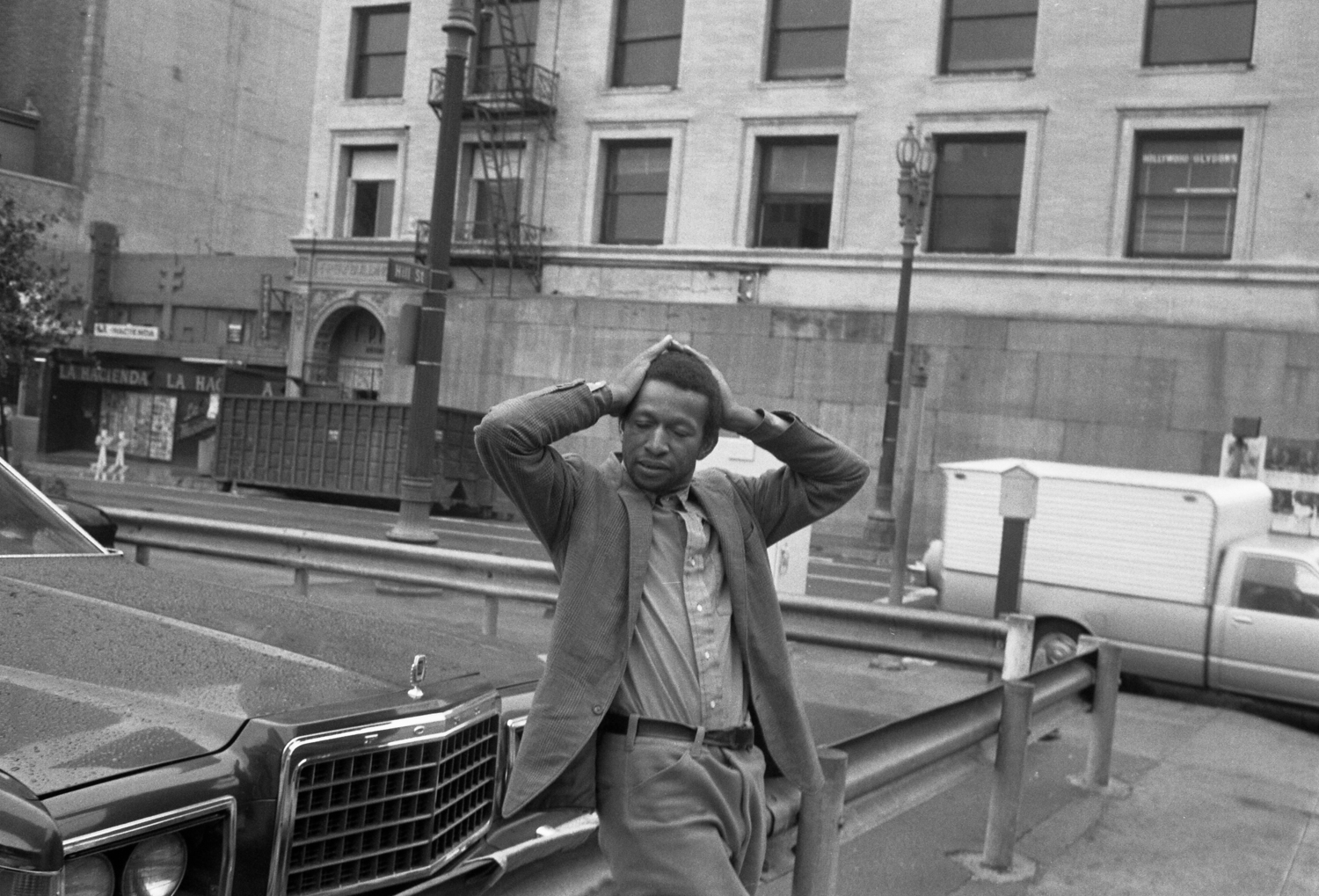

Steinmetz’ own images from this period certainly bear the stylistic hallmarks of the serendipity of classic street photography, where small moments, gestures, and juxtapositions create single frame vignettes, so clearly he was well aware of the history of the genre. And if there is any telltale sign of Winogrand’s indirect influence in these early pictures, it is the touch of social darkness that inhabited Winogrand’s late work, filtered through Steinmetz’ eye for composition; to my eye, there is just a hint more of this deflating mood here than in what Steinmetz would produce later (this is his ninth book with Nazareli).

Like any newcomer to LA, Steinmetz hits on the surfaces that give the city its distinct character. He catches the lilting grace of a roller skater lost in the music. He frames the sun-baked freeways against an impenetrable smoggy sky. He tracks the bored gaze of a child at an enchilada stand. He revels in the sparkled mist of lawn sprinklers. And he collapses the jolting contrast of a fake Christmas tree and arcing palm fronds. While these are geographic themes we have seen before and since, Steinmetz delivers them with a visual maturity unusual for his young age.

Steinmetz seems more at home capturing the fleeting eccentricities of the everyday, especially when a portrait coalesces inside unexpected surroundings. An older man stands on the sidewalk, framed by a narrow band of chainlink fence as thought trapped in a tightening vise. A mechanic ponders the dense cloud of mysterious smoke coming from his garage. A father emphatically tells his tiny daughter in frills of white to go the other way. A young girl hanging out a car window examines the bent over backside of someone rooting in the gutter. And a man seemingly passed out underneath a picnic table hangs on to the wooden bench with weary heaviness.

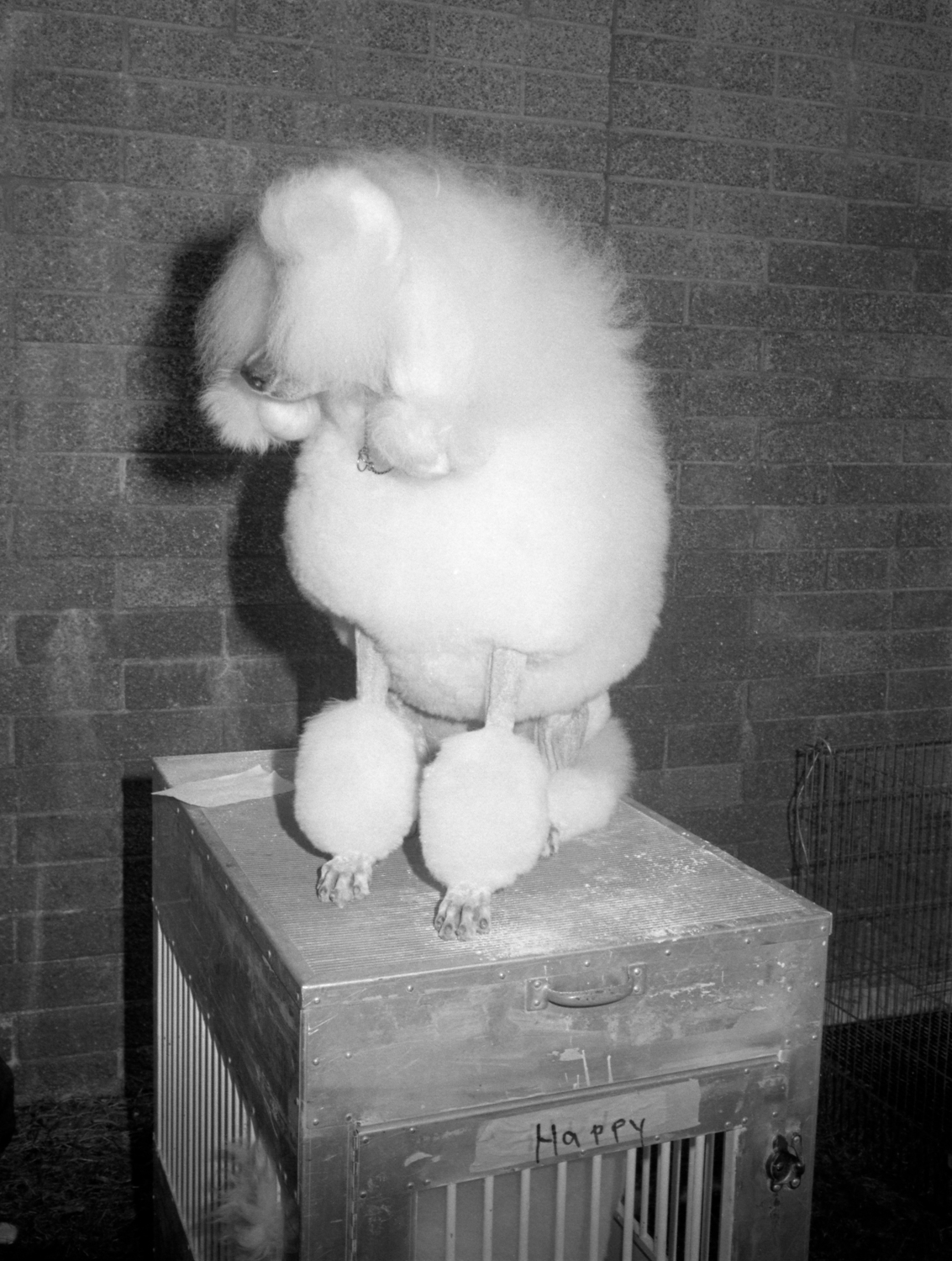

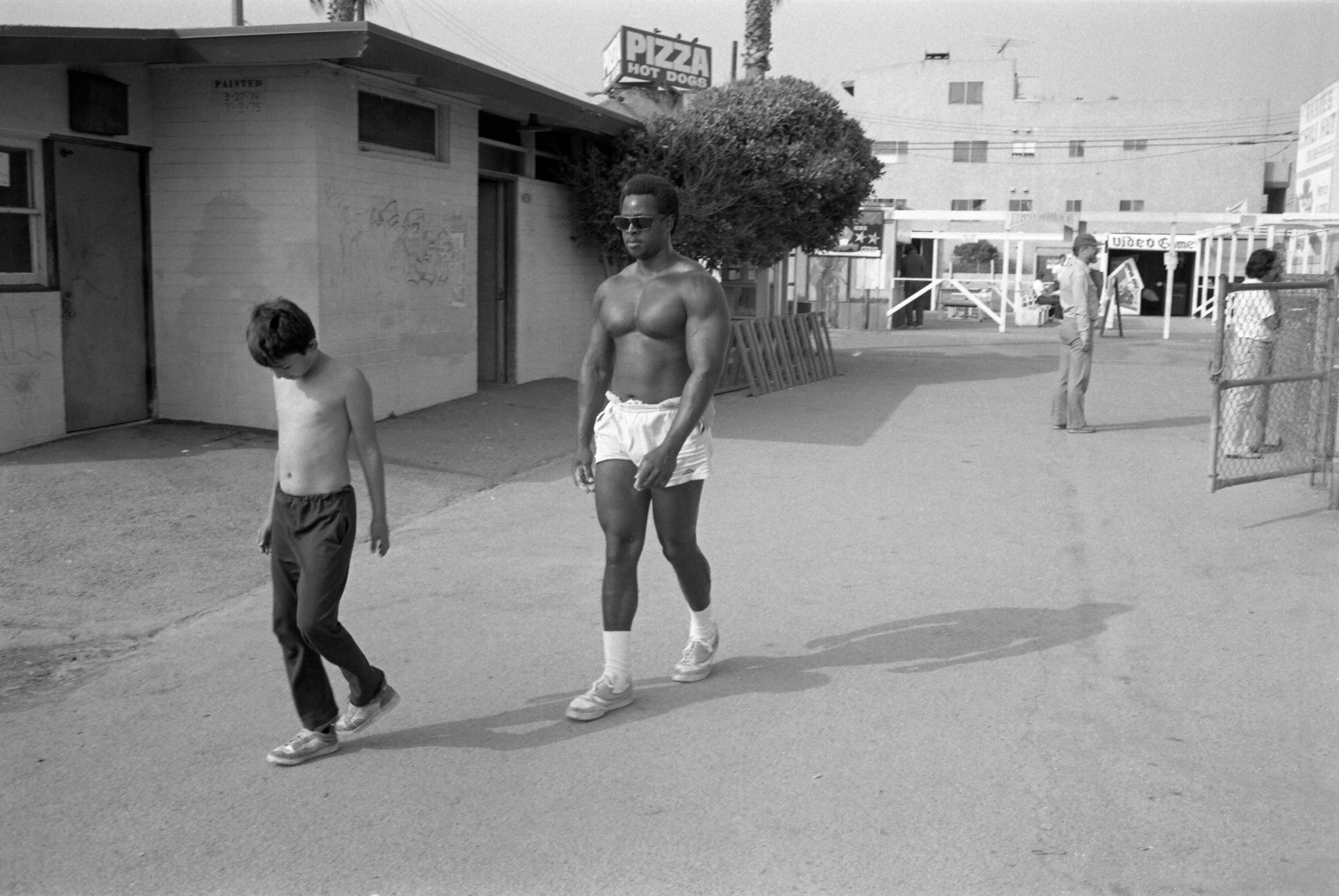

Compositionally, we can see Steinmetz expanding his angles and views, testing different techniques. He explores width in shots that capture the alignment of a rock in the dirt with a far off VW bug and the expanding distance between a man crossing the street and another sitting by the roadside. He plays with fences as barriers, cast self portrait shadows, fabric patterns (the checked shirts of triplet girls, the animal print pants of an elderly shuffleboard player) and beams of sunlight that catch a woman’s face or hair. He tries out the extremes of light and dark, using sun-blasted white apartments as a backdrop, the shiny dark back of a truck as foreground interruption, and the limitless darkness of a sidewalk sinkhole in the bright afternoon as a central subject. Even Steinmetz’ understated visual humor starts to emerge, allowing the contrast of a skinny boy and a muscled man walking nearby, the poofiness of a fuzzy poodle named Happy, or the heart-shaped bent branches of a suburban tree to deliver their comedy with quiet reserve.

As photobooks go, this is one where sophisticated design focuses attention on the superlative photography, rather than distracting from it. The monograph’s production values are simply immaculate – gorgeous large reproductions given enough white space to breathe, an elegant gold slipcase, and sequencing that deftly shows us patterns and connections in the pictures. It is positively regal in its celebration of these photographs, and luckily enough, Steinmetz’ pictures deserve this kind of perfection of presentation.

That Steinmetz made such consistently excellent work as a 21 year old is hugely impressive. Even if we attribute some of his developing talent to the osmosis effects of Winogrand’s approach to the medium, the pictures we might deem derivative in some manner actively (and knowingly I think) push to get beyond fawning homage. This one of those photobooks that is so much better than we might initially realize – the photographs provide a compelling bridge between the broad-based influences Steinmetz was raised on and the places he was to go later, and that artistic evolution is an intricate and layered story. The photobook delightfully integrates unexpectedly informative and often great pictures into a lovingly crafted and well produced object, offering a rare glimpse of a previously unexplored chapter in Steinmetz’ long career.

Collector’s POV: Mark Steinmetz is represented by Yancey Richardson Gallery in New York (here) and Charles A. Hartman Fine Art in Portland (here). Steinmetz’ prints aren’t consistently available in the secondary markets – only a handful of prints have been sold at auction in the past five years. As such, gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.